A Cost-Based Decision Framework for Software Engineers

As software engineers, we’re constantly faced with a barrage of decisions. From architectural choices to feature prioritization, and even down to how we approach a specific coding problem, each one carries weight and can significantly impact the trajectory of a project. Over the last year, I’ve honed a cost-based decision framework that has proven invaluable, providing clarity and confidence, particularly in the often-chaotic discovery and implementation phases of a project.

I started leveraging this approach heavily when kicking off a large-scale project where I had identified over 50 key decisions. With discovery being paramount, it was simply infeasible to thoroughly research every single decision before launching a prototype or beta to gather crucial user feedback. This forced a pragmatic approach to decision-making.

At its core, this framework hinges on understanding two fundamental types of costs:

The Cost of Making the Wrong Decision: This refers to the negative consequences that arise from committing to a suboptimal path. These can be direct or indirect, and often compound over time.

The Cost of Delaying a Decision: This is the value lost or cost incurred by not making a decision in a timely manner. It represents missed opportunities, prolonged uncertainty, and potential setbacks.

My guiding principle has become: whenever you can delay a decision, you should. Why? Because waiting often allows you to gather more information, observe real-world outcomes, and reduce uncertainty, thereby increasing the likelihood of making a better decision. However, this isn’t a blanket rule. If delaying a decision means sacrificing significant value, such as a critical business opportunity or market advantage, then making an early, albeit potentially less informed, decision is the wiser course of action.

Let’s dive deeper into these two costs:

Understanding the “Cost of Wrong Decision”

The cost of a wrong decision can manifest in various ways:

Rework and Reruns: Implementing something incorrectly means time and effort spent building it, only to tear it down and rebuild. This directly wastes engineering resources.

Technical Debt Accumulation: Poor architectural choices or rushed implementations often lead to technical debt, which incurs ongoing costs for maintenance, slower future development, and increased bug fixing.

Performance Issues and Scalability Limitations: A wrong decision in system design can lead to poor performance, hindering user experience and potentially requiring costly refactoring or infrastructure upgrades later.

Security Vulnerabilities: A flawed security decision can lead to breaches, data loss, reputational damage, and significant legal and financial repercussions.

Loss of Business Opportunity: If a product or feature is built incorrectly, it might fail to meet market needs, leading to lost revenue or market share.

Impact on Team Morale: Repeatedly working on things that get thrown away, or battling against fundamental design flaws, can significantly demoralize a team.

Quantifying this cost can be challenging, as some impacts are indirect or long-term. However, even a qualitative understanding of the potential fallout is crucial.

Deconstructing the “Cost of Delay”

The cost of delay, often underestimated, can be equally, if not more, impactful:

Lost Revenue/Business Value: If a feature or product could generate revenue or deliver significant business value, every day of delay means lost income or competitive advantage. Think of a critical compliance feature or a new product that unlocks a new market segment.

Missed Market Opportunities: In fast-moving industries, being late to market can mean missing a window of opportunity entirely, allowing competitors to gain a foothold.

Increased Project Costs: Delays can lead to extended team allocation, prolonged infrastructure usage, and increased overheads, directly inflating project budgets.

Erosion of Customer Trust/Satisfaction: Users expect continuous improvement and new features. Delays can lead to frustration and a perception of stagnation, potentially driving users to alternatives.

Dependency Blockers: Delaying a decision on one component can block progress on multiple dependent features or teams, creating a cascading effect of delays across the organization.

Increased Uncertainty: The longer a decision is delayed, the more uncertain the path forward becomes, making future planning more difficult and introducing more risk.

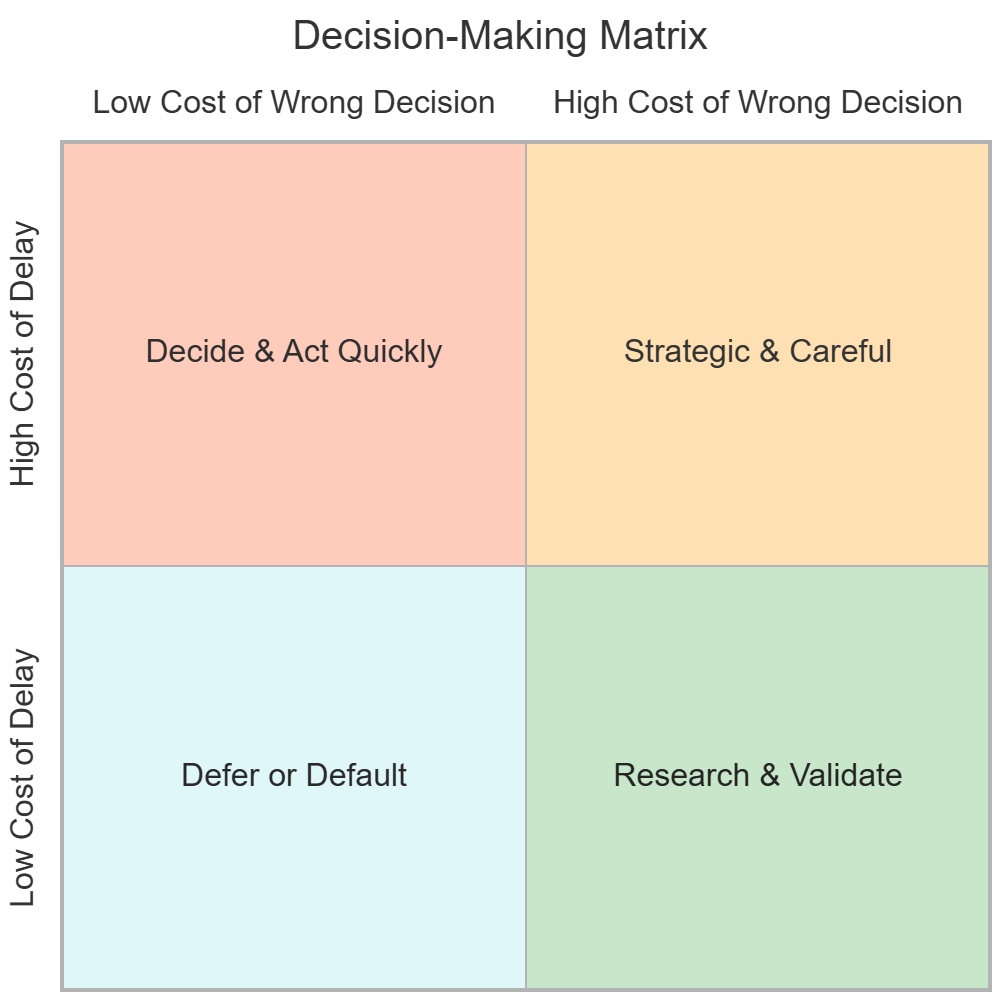

The Decision Matrix: Cost of Delay vs. Cost of Wrong Decision

To make this framework actionable, we can visualize these two costs in a simple 2x2 matrix:

Let’s break down each quadrant:

Low Cost of Delay, Low Cost of Wrong Decision (Defer or Default)

Description: Decisions here typically involve minor details or reversible choices where the impact of being wrong is small, and waiting doesn’t significantly hinder progress.

Action: Defer the decision until more information is naturally available, or default to a reasonable path if a quick decision is needed. Examples: Minor UI tweaks, naming conventions for internal variables, or initial logging levels. These can be iterated on easily.

Low Cost of Delay, High Cost of Wrong Decision (Research & Validate)

Description: These are decisions where the immediate impact of not deciding isn’t high, but getting it wrong could have significant negative consequences.

Action: Invest time in thorough research, prototyping, and validation. Seek expert opinions, conduct experiments, or run small proofs-of-concept. Examples: Choosing a core database technology, selecting a major third-party integration, or defining a critical API contract that will be used by many consumers.

High Cost of Delay, Low Cost of Wrong Decision (Decide & Act Quickly)

Description: This quadrant often contains decisions that are time-sensitive but where the consequences of being wrong are relatively contained and reversible.

Action: Make a decision swiftly, even with imperfect information. Prioritize getting something out to learn and iterate. Bias towards action. Examples: Launching an MVP with a core feature set, deciding on a rapid marketing campaign, or making an urgent bug fix that unblocks critical business operations. The “fail fast, learn fast” mentality thrives here.

High Cost of Delay, High Cost of Wrong Decision (Strategic & Careful)

Description: These are the big, high-stakes decisions. Delaying them has significant negative consequences, but so does getting them wrong. This is the highest priority quadrant.

Action: These require careful consideration, senior stakeholder alignment, and potentially phased rollouts or robust rollback plans. Mitigation strategies for both delay and error are paramount. Examples: Major architectural paradigm shifts (e.g., monolith to microservices), large-scale platform migrations, or entering a completely new product market.

Implementation Cost

The “cost of a wrong decision” and “cost of no decision” also need to be evaluated against an implementation cost. Here’s were we find some rough edges in this framework and where the highest potential for improvements (or even just improved rationale).

From low Cost of Delay (No) Decision we still need a way to understand if we should default or defer. Using an implementation cost is one way to improve that decision. Cost of Wrong Decision is in to some extent dependent on the imagined implementation. But I’ve found that contrasting to the implementation cost is, currently, the best approach to getting to a guiding result.

External vs. Internal Costs

While actively using this framework I realized that I needed to understand who to involve to make a sound decision. To assist with that I introduced the split between external and internal costs.

External Costs are incurred by parties outside your business, such as customers or partners. These could include a customer experiencing an issue that requires them to spend hours instead of minutes to complete a task, a vendor being unable to integrate with a new API, a loss of brand reputation from a security breach, or a drop in customer conversion rates.

Internal Costs are those experienced by the business itself. This includes everything from wasted engineering effort and missed market opportunities to increased operational overhead (like higher cloud bills), reduced team morale due to technical debt, and licensing fees for incorrect tool choices.

Practical Approach with a Decision Scorecard

While a simple 2x2 matrix is great for high-level thinking, we can use a scorecard to handle more variables and quantify decisions. This helps us prioritize and make trade-offs on a more granular level.

My approach has been to build a spreadsheet with all project aspects and rate each on a logarithmic scale (e.g., 1, 10, 100, 1,000). Using a logarithmic scale helps us differentiate between low-impact and high-impact costs, preventing a single major cost from being obscured by a series of minor ones. Since it’s difficult to quantify costs to the exact value, the logarithmic scale accepts that we are dealing with estimates largely based on experience or short research (like 30 minutes or so).

Here’s an example:

AspectImplementation costInternal cost of wrong decisionExternal cost of wrong decisionInternal cost of no decisionExternal cost of no decisionData validation & sanitisation100010010010001000API Traffic routing1001010010001000API Deployment100100110001Logging and monitoring1010110001Scalability and performance optimization100101001010Caching1010101010

Using this scorecard, we can calculate a Research Priority Score for each aspect, helping us decide where to invest our discovery efforts. We calculate this by multiplying the relevant costs, which highlights where a wrong decision would have a significant negative impact.

By analyzing the scorecard, we can then apply the principles from our decision matrix:

For aspects with a high Research Priority Score (like “Data validation & sanitisation”), we should treat them as Quadrant 2: Research & Validate. This is where we should invest in deep discovery, like collaborating with a UX researcher or creating RFC design documents for engineering feedback.

To accelerate time to market, we should identify aspects with a high cost of no decision but a low cost of wrong decision. These fall into Quadrant 3: Decide & Act Quickly. For “API Deployment” and “Logging and monitoring,” the low

External cost of wrong decisionmeans we should quickly find a solution and move forward.Finally, we can find aspects with low costs across the board. These fall into Quadrant 1: Defer or Default and can be ignored for now. For example, “Caching” and “Scalability” both have relatively low scores, so we can defer these until they become necessary.

Applying the Framework to Everyday Coding

This cost-based decision framework isn’t just for high-level project planning; it’s a powerful tool for improving efficiency in our day-to-day coding too, primarily as a mental model rather than requiring a spreadsheet analysis. How often have you found yourself stuck trying to find the perfect solution to a problem, only to realize you’ve spent hours deliberating when a “good enough” solution would have unblocked you much faster?

Consider a complex function you need to write:

Cost of Delay: Every minute you spend agonizing over the most elegant, highly optimized algorithm is time not spent delivering value. If the immediate need is to just get the feature working, the cost of delaying a functional solution can be high (e.g., blocking other features, missing a deadline).

Cost of Wrong Decision: How bad would a less-than-perfect solution be? If it’s an internal utility that only runs occasionally with small data sets, the “wrong” decision (e.g., a slightly less efficient algorithm) might have a very low cost. If it’s a core performance-critical component, the cost of being wrong is much higher.

This framework encourages us to make pragmatic choices:

Sometimes “Good Enough” is Best: If the cost of delay is high, and the cost of a slightly imperfect solution is low (e.g., it can be refactored easily later, or the performance impact is negligible for current scale), then choose a “decent” solution and move on. Don’t let the pursuit of perfection become the enemy of progress.

Prototype for High-Impact Decisions: If you’re unsure about the best approach for a critical piece of code, don’t over-engineer upfront. Quickly prototype a few options. The “research and validate” quadrant applies here: the cost of delaying the final implementation is low, but the cost of getting the fundamental approach wrong is high. A quick prototype drastically reduces that risk.

Prioritize Learnings: Often, getting a working solution, even if it’s not ideal, allows you to gather real-world data and feedback. This new information can then guide a better, more informed decision for future iterations.

By consciously applying this cost-based framework, software engineers can move beyond intuition, make more informed choices, and ultimately drive more successful outcomes for their projects and organizations. It empowers us to be not just technical contributors, but strategic problem-solvers.